RIO DE JANEIRO (AP) ‚ÄĒ A 27-year-old Brazilian woman, who said she became pregnant after being raped in March during in Brasilia, should have been granted access to a legal abortion. But when she sought to terminate the pregnancy at a hospital around a month later, she was told she needed a police report to access the service, despite it not being a legal requirement.

She decided to abort at home with medication she bought on the black market, with only a few friends on site to help.

‚ÄúI fainted several times because of the pain. I was terrified I was going to die,‚ÄĚ she said.

The Associated Press does not identify people without their permission if they say they have been sexually assaulted.

In , abortion is legally restricted to cases of rape, life-threatening risks to the pregnant woman or if the fetus has no functioning brain. Theoretically, when a pregnancy results from sexual violence, the victim’s word should suffice for access to the procedure.

‚ÄúThe law doesn‚Äôt require judicial authorization or anything like that,‚ÄĚ explained Ivanilda Figueiredo, a professor of law at the State University of Rio de Janeiro. ‚ÄúA woman seeking an abortion recounts the situation to a multi-disciplinary team at the healthcare clinic and, in theory, that should be enough.‚ÄĚ

In practice, however, advocates, activists and health experts say to ending a pregnancy even under the limited conditions provided for by the law. This is due to factors including lack of facilities, disparities between clinic protocols and even resistance from medical personnel.

‚ÄúHealthcare professionals, citing religious or moral convictions, often refuse to provide legal abortions, even when working in clinics authorized to perform them,‚ÄĚ said Carla de Castro Gomes, a sociologist who studies abortion and associate researcher at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro.

Women in Brazil also face geographical barriers to legal abortions. Only 290 facilities in a mere 3.6% of municipalities around the country of approximately 213 million people provide the service, according to a 2021 study from scientific journal Reports in Public Health.

In June 2022, four nonprofits filed a legal challenge with the Supreme Court, arguing that restrictions on abortion access violate women’s constitutional rights. The case is currently under review.

‚ÄėStill a taboo‚Äô

A 35-year-old cashier from a small city in the interior of Rio de Janeiro state also said she became pregnant as a result of a rape. But, unlike the woman in Brasilia, she chose to pursue an abortion through legal means, fearing the risks that come with a clandestine procedure.

Although Brazil’s Health Ministry mandates that, in the case of a pregnancy resulting from rape, healthcare professionals must present women with their rights and support them in their decision, the woman said a hospital committee refused to terminate the pregnancy. They claimed she was too far along, despite Brazilian law not stipulating a time limit for such procedures.

She eventually found help through the Sao Paulo-based Women Alive Project, a nonprofit specializing in helping victims of sexual violence access legal abortions. The organization helped her locate a hospital in another state, an 18-hour drive, willing to carry out the procedure.

Thanks to a fundraising campaign, the woman was able to travel and undergo the operation at 30 weeks of pregnancy in late April.

‚ÄúWe are already victims of violence and are forced to suffer even more,‚ÄĚ she said in a phone interview. ‚ÄúIt‚Äôs a right guaranteed by law, but unfortunately still seen as taboo.‚ÄĚ

Legal uncertainty

Brazil‚Äôs abortion laws are among the most constrictive in Latin America, where several countries ‚ÄĒ including , and ‚ÄĒ have enacted sweeping reforms to legalize or broadly decriminalize abortion.

This legislative environment is exacerbated by a political landscape in which far-right politicians, supported by Catholic and Evangelical voters who make up a majority in the country, regularly seek to further restrict the limited provisions within the country's penal code.

In 2020, the government of far-right former President issued an ordinance requiring doctors to report rape victims seeking abortions to the police. Current President revoked the measure in his first month in office in 2023.

But the measure left lasting effects.

‚ÄúThese changes end up generating a lot of legal uncertainty among health professionals, who fear prosecution for performing legal abortions,‚ÄĚ Castro Gomes said.

Last year, conservative lawmaker Sóstenes Cavalcante proposed a bill to equate the termination of a pregnancy after 22 weeks with homicide, across Brazil. The protests ultimately led to the proposal being shelved.

But in November, a committee of the Chamber of Deputies approved a proposed constitutional amendment that would effectively outlaw all abortions by determining the ‚Äúinviolability of the right to life from conception.‚ÄĚ The bill is currently on hold, awaiting the formation of a commission.

Earlier this month, Rio Mayor Eduardo Paes, a Lula ally, came under fire after sanctioning a bill mandating anti-abortion messages on posters in municipal hospitals and other health establishments.

‚ÄėDoctors don‚Äôt tell you‚Äô

Advocates say access to abortion highlights significant disparities: women with financial means dodge legal restrictions by , while children, poor women and Black women face greater obstacles.

According to the Brazilian Forum on Public Safety, 61.6% of the 83,988 rape victims in 2023 were under the age of 14. A statistical analysis that year by investigative outlet The Intercept estimated less than 4% of girls aged 10 to 14 who became pregnant as a result of rape accessed a legal abortion between 2015 and 2020.

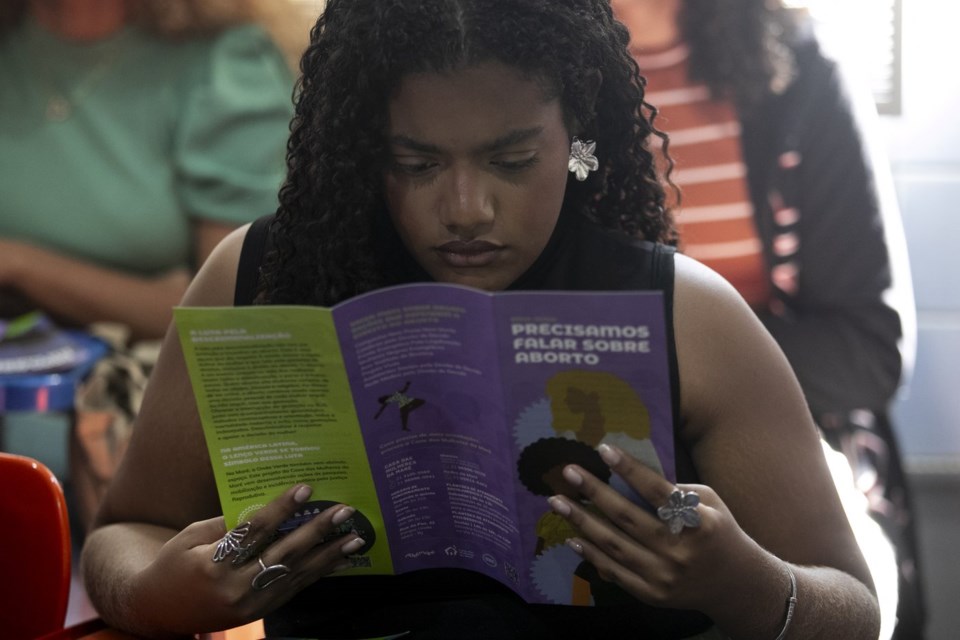

In Rio de Janeiro’s Mare , one of the city’s largest low-income communities, the nonprofit Networks of Mare’s House of Women provides women with information regarding their reproductive rights, including legal provisions for abortions.

It was there, during a recent workshop, that Karina Braga de Souza, a 41-year-old mother of five, found out abortion is legal in certain cases in Brazil.

‚ÄúWe don‚Äôt have access (to information). Doctors don‚Äôt tell you,‚ÄĚ she said.

Cross-border connections

Feminist groups in Brazil are campaigning at a federal level for enhanced access to legal abortion services.

Last year, ‚ÄúA Child Is Not a Mother,‚ÄĚ a campaign by feminist groups, successfully advocated for the National Council for the Rights of Children and Adolescents to adopt a resolution detailing how to handle cases of pregnant child rape victims. The body, jointly made up of government ministries and civil society organizations, approved the resolution by a slim majority in December.

Brazilian activists also are seeking to improve access to abortion by forging links with organizations abroad.

In May, members of feminist groups in Brazil including Neither in Prison, Nor Dead and Criola met with a delegation of mostly Black U.S. state legislators. The meeting, organized by the Washington, D.C.-based Women’s Equality Center, aimed to foster collaboration on strategies to defend reproductive rights, especially in light of the to strip away the constitutional right to abortion.

In the meantime, the consequences for women who struggle to access their rights run deep.

The woman in Brasilia who underwent an abortion at home said she is coping thanks to therapy and the support of other women, but has been traumatized by recent events.

By being denied access to a legal abortion, ‚Äúour bodies feel much more pain than they should,‚ÄĚ she said. ‚ÄúWhenever I remember, I feel very angry.‚ÄĚ

___

Follow AP’s coverage of Latin America and the Caribbean at .

Eléonore Hughes, The Associated Press